PhilHealth

home | contact us | sitemap | disclaimer

News

Lessons on Universal Health Coverage (UHC)

from Japan

December 8, 2015

TOKYO, Japan --- Mandatory health insurance coverage, provision of necessary medical care services, a controlled fee schedule and continued economic growth. All these have enabled Japan to achieve and sustain universal health coverage (UHC) for over 50 years now.

These important elements were among the modules taken up in a two-week training recently organized by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) in collaboration with the National Institute of Public Health to strengthen social security systems towards UHC in Asia. The training, which was attended by 16 participants from Bangladesh, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Vietnam, was aimed at sharing Japan’s own journey towards UHC.

Everyone must be covered

As early as 1956, the Japanese government already acknowledged the need to have a comprehensive health insurance program that will cover the entire population. Through five (5) different coverage schemes, Japan’s 127 million citizens are assured of quality health care anywhere in the country.

Civil servants are covered through Mutual Aid Associations while employees of large corporations are covered by Health Insurance Societies. Employees of small and medium enterprises are covered by the Japan Health Insurance Association, while citizens who are 75 years old and above have the Medical Care System for the Elderly to rely on. The informal sector and those under the welfare system are cared for by the National Health Insurance. Over 3,000 insurers make it possible for Japan’s citizens to be provided with health insurance coverage.

Premium matters

How much do the citizens pay as health insurance premium? It depends on their age and ability to pay. While the amount of premium contribution is determined by the insurer, generally, employees pay a fixed percentage of their monthly wages and bonuses as premium. Working spouses contribute double. On the other hand, the informal sector insured pay a fixed percentage of their annual household income that includes the fixed premium per beneficiary and real estate taxes whenever applicable. Payment is made six (6) times a year and while penalties or surcharges are not imposed on delayed premium payments, the government may confiscate an insured’s assets after exhausting all available measures to collect.

Service delivery infrastructure

All insured citizens may avail themselves of basic health services that are deemed medically necessary and appropriate anywhere in Japan. With over 15,000 medical institutions scattered all over the country, Japan has more than enough resources to deliver health care services. About 80 percent of all hospitals and 95 percent of all clinics are run by the private sector, but these are all non-profit, meaning revenues generated from hospital operation and management cannot be distributed to shareholders; rather, these revenues must be used to upgrade medical equipment and to invest in expansion initiatives. Facilities need no accreditation from any of the insurers to be able to grant benefits to the insured, but some facilities are already ISO-certified and others have taken the quality management step a notch higher by acquiring Joint Commission International (JCI) accreditation.

The number of doctors and nurses working in these facilities is continuously rising, almost in direct proportion to the number of medical schools in the country.

Necessary medical services

The two-week training included a visit to Kurosu Hospital, a private, 45-bed hospital in the Hatagaya District where participants observed the admission procedure for inpatient and outpatient services. Of primary importance at the receiving section is the need to establish a citizen’s health insurance coverage which will then become the basis for the patient’s share in the total medical cost. The insured helps shoulder the financial burden of medical treatment, a practice deeply rooted in the Japanese culture of shared responsibility.

Each patient has his own dossier and the admission data are sent electronically to the doctor’s clinics under an ordering system. The procedure ends with a patient settling his co-payment before being discharged.

Both inpatient and outpatient medical care services are paid for by the insurer, based on a fee schedule approved at the Cabinet level. The fee schedule, which is used by public and private providers, as well as by all insurers in the country, is updated every two years.

Community care services

Japan’s population is fast turning grey. Its elderly population comprises 26.7 percent of its 127 million population, and is expected to reach 40 percent by 2050. This year, the country is expecting about 32,000 new centenarians. With fertility rate at 1.42 and a natural decline of 270,000 in 2014, the population is expected to decline further to 100 million by 2050. It has a limited migration quota, accommodating just enough migrants to “refill” the 270,000 lost annually through natural progression. The situation has been ongoing for the last ten (10) years. In fact, managing its aging population is now becoming the country’s biggest challenge.

To better appreciate how Japan takes care of its elderly, the trainees were taken to Ogano town, a community surrounded by mountain ranges in the Saitama Prefecture. The town’s integrated community care services make life for the “young old” (those aged 65 to 74 years old) and the “old old” (those 75 years and older) a whole lot better in an environment that they are used to. Around 32.08 percent of the town’s 13,000 population are senior citizens, with almost 18 percent of the number considered "old, old."

The town’s elderly population is assessed vis-a-vis their qualification into the Long-Term Care Insurance Program. Once admitted into the LTC program, they are entitled to medical services in the community hospital, ranging from diagnostic, curative and maintenance services, all covered by health insurance. The town has tapped the services of its welfare workers who regularly visit the elderly population who are living alone to provide the necessary assistance, from preparing meals, giving the elderly a bath, cleaning the house, doing the laundry, and making sure that the elderly is comfortable. For such a unique partnership in caring for the town’s older population, Ogano has won the 56th Health Culture Award in 2004 for its integrated community care services.

Honor, trust and integrity

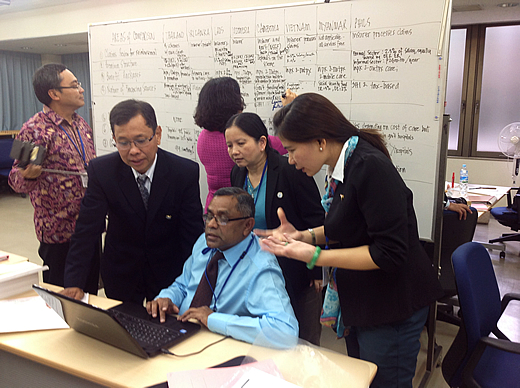

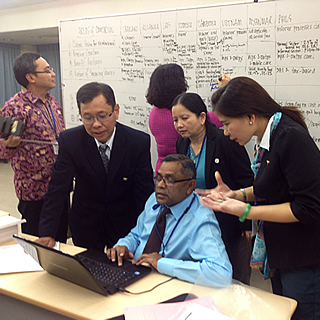

As the training progressed into its second week, the participants were brought to the Yamanashi Prefectural Federation of National Health Insurance Insurers to observe how the medical benefit claims are reviewed, evaluated and decided upon for payment. The Federation is entrusted by insurers such as municipal governments, to provide the administrative services pertaining to the assessment and reimbursement of health insurance claims submitted by health insurance-covered medical institutions.

There, the participants were able to see how online review of claim documents was done. Around 98 percent of claims are electronically processed; the remaining two percent come from small clinics managed by old physicians who are technology-averse.

Discussions with panellists also revealed that to date, none of the over 3,000 insurers in Japan has defaulted in the payment of claims despite the guarantee provided for by banks. Interestingly, there is also no governing entity that monitors the financial liquidity of these insurers to ascertain their capability to pay the Federation for each good claim processed, and the millions of Japanese citizens insured with them.

Robust economic growth

The lessons gained from World War II has taught Japan and its people to be more resilient, more self-reliant and focused. The years spanning 1945 to 1955 were devoted to massive recovery and reconstruction during which the municipalities eventually became the insurers of the Community-Based Health Insurance Law and the government started subsidizing benefit payments. At the same time, its economy rapidly grew and by 1956, it achieved the highest level of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita. By 1958, the Community-Based Health Insurance Law was revised which led to the establishment of the mandatory insurance coverage in all municipalities in April 1961 when universal health insurance coverage was attained.

In 2013, the country’s health expenditure as share of GDP was at 10.2 percent, higher than the 8.9 percent OECD average. Despite its increasing coverage for health care, Japan is able to fulfil its commitments to its citizens by collecting taxes properly and by not going in the way of other countries that resort to overseas borrowing at high interest rates. With a robust economy, Japan is able to continue financing its health care initiatives.

As the world’s third largest donor country in health, Japan is poised to continue contributing significantly to global efforts to push quality of life through a healthy citizenry. Its basic design for peace and health puts emphasis on the need to strengthen health systems to attain human security, promote UHC and contribute some more to global health using Japanese expertise and experience, medical products and technologies. For the meantime, Japan shares with the rest of the world how it was able to achieve UHC, for other countries to possibly replicate. (END) (Maria Sophia B. Varlez)